Find Your Perfect Recipe Here

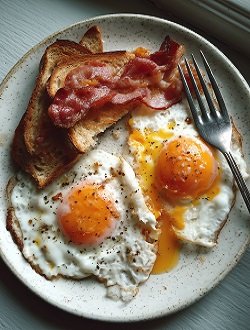

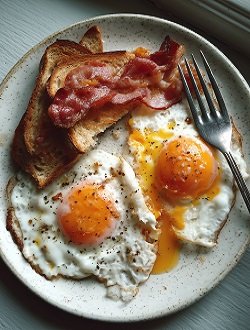

Newest Recipes

Try something new! Check out our latest, quick and easy, family-friendly recipes.

🌟 aires #1 Recipe

Mini Pecan Cups with Frosting – A Bite-Sized Southern Delight

Desserts Breakfast Drinks Salads Breakfast Desserts Drinks Main Dishes Find Your Perfect Recipe Here Bread Breakfast Food Dinners Drinks Healthy Dishes Easy Salad All Recipes … Read more

Get the recipe!explore

Hey, I’m Emily Carter!

Hey y’all! I’m Emily Carter, a 36-year-old home cook, recipe wrangler, and proud Southern gal living just outside of Austin, Texas. My kitchen is my happy place—usually smelling like cinnamon, garlic, or something buttery in the oven. I believe that good food doesn’t need to be fancy, it just needs to be made with heart. . .

About UsEasy Dinner Ideas

Solving the what’s-for-dinner dilemma with flavorful weeknight meals. Simple and delicious recipes to make dinnertime stress-free.

Get new recipes sent to your inbox!

Be the first to get new recipes! Plus, extra tips and treats delivered right to your inbox!